Collective Blame and the Media's Role in Prevention

Research into the effects of 'collective blaming' of ethnic and religious groups for acts of violence suggests that reciprocal acts against innocents can occur as a result. The media's role in this process is vital, as demonstrated by a series of experiments conducted using news clippings that showed collective blame to be undermined when its hypocrisy was highlighted.

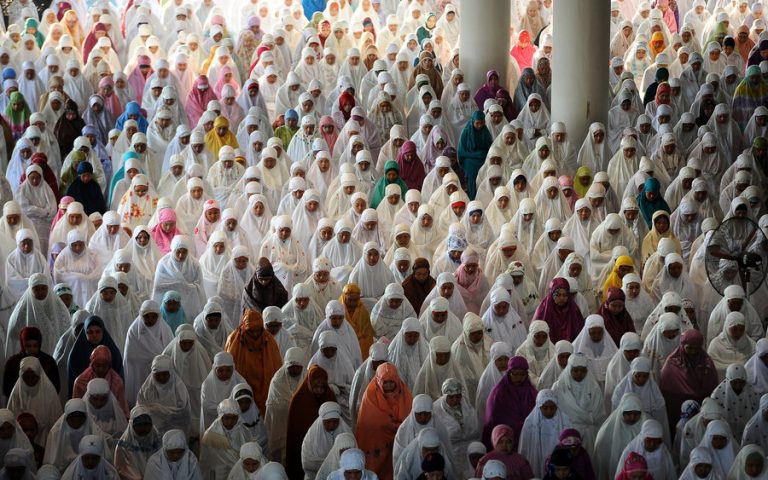

In response to the President's retweet of an anti-Muslim video on Twitter, Vox published a profile of this research and conducted an interview with Emile Bruneau, one of the researchers involved, to discuss how collective blame leads to dehumanization and ultimately policies that are harmful to minorities such as Muslims.

Professor Bruneau spoke to the Media and Peacebuilding Project to elaborate on his comments and explain further how the media can act as both a help and a hindrance when it comes to collective blame.

Q: Do you have any ideas for how your research could guide media actors in shaping narratives about groups?

A: Three lines of my recent research speak to this. The first is on ‘meta-perceptions’ (how we think another group thinks of our group), and ‘meta-dehumanization’. In general, Americans have strong perceptions that Muslims and Muslim groups (Iranians, Palestinians) dehumanize and dislike us. And these perceptions have consequences. For example, the more Americans think Iranians dehumanize ‘us’, the more they oppose the Iranian Nuclear Accord, and the more they support open warfare against Iran. However, when we sample Muslim groups, they report much more respect for America and Americans than we think. I imagine that these negative meta-perceptions are driven by the media. In fact, I felt this when I first went to Palestine to conduct research in 2009. I had never met a Palestinian, and when I arrived in the West Bank I was pretty nervous, and convinced that I would be universally despised. My experiences quickly dispelled these perceptions as I was treated with warmth and respect everywhere I went. I have now been there for three summers, and never experienced any of what I expected based on media accounts. So the media could better report the actual views of other groups towards our own.

Second, converging with previous research, I’ve found that the degree to which people support the ‘underdog’ in a conflict is heavily tied to how violent that group is perceived to be. If we see the underdog group as inherently violent, our support for them evaporates. The media often cover only the most extreme and violent efforts by a group (e.g., Palestinians), which shapes the narrative and erodes sympathy and support. When I showed a trailer to a documentary depicting an ongoing Palestinian non-violent campaign, attitudes and behavior towards Palestinians improved (without eroding attitudes towards Israelis).

Third, my recent research on collective blame suggests that stories that try to directly induce empathy towards another group are less successful than interventions that challenge underlying assumptions and beliefs about that target group. Although I have not tested this yet directly, my hypothesis is that people refuse to mobilize their empathy towards another group if they think that other group does not deserve their empathy. The best way to reaching someone’s heart may be by first changing their mind. My recent work with an intervention tournament suggested this to be the case.

Q: What are the ethical obligations of journalists for ensuring collective blame cycles are not continually perpetuated?

A: The research I presented suggests that gently reminding people that they do not hold other groups responsible for the actions of group extremists if effective at checking their blame of Muslims for violence committed by a Muslim extremist. However, taking the less than gentle approach of ‘calling out hypocrisy’ and trying to shame the other side will likely backfire.

In his Vox interview, Bruneau highlights how hypocrisy, when deployed in the correct way, as the most successful method in preventing collective blame cycles from being exacerbated. Other visual stimuli, depicting Muslims as upstanding members of society and generally attempting to humanize them to the audience, did not counteract collective blame as successfully as the hypocrisy method.

Content used to induce this feeling of hypocrisy included:

-A Muslim woman on a news network complaining that Christians are never collectively blamed for the violence of an individual.

-Reading passages from the Old Testament as though they were Quranic verse, later to be revealed as Biblical.

-Asking participants to 'rate' how much blame should be assigned to innocent Muslims in various locations and professions for acts of terrorism.

As Bruneau points out in his comments in this interview also, hypocrisy cannot be deployed as a weapon without leading the audience to the conclusion needed to overcome their prejudice. The examples used in his research revealed that subtly exposing hypocrisy using the stimuli mentioned was the most effective tool.

Q: Could your research be applied to those of political parties, i.e. avoiding blaming Democrats or Republicans for the actions of an individual?

Absolutely. I’m focusing on this research now.

Q: Do you know of any examples where narratives of collective blame have been successfully disrupted, as part of peacebuilding efforts? How did they achieve this?

I haven’t seen peacebuilding efforts focusing on collective blame. I don’t think it is on their radar. Generally, peacebuilding efforts are focused on empathy and trust. Which is potentially the problem – if you don’t address the biases that may be hindering empathy and trust, people may be resistant to ‘trust-building’ and ‘empathy-building’ efforts.

Emile Bruneau is a research associate and lecturer at the Annenberg School of Communication at the University of Pennsylvania. He is the lead scientist at the Beyond Conflict Innovation Lab. He has worked in conflict zones in Ireland, Palestine and Sri Lanka.